Why Vinod Khosla, Richard Branson,Bill Gates are betting heavily on ETHANOL

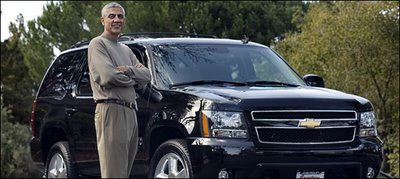

VINOD KHOSLA was a founder of Sun Microsystems and then, as a partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, the Silicon Valley venture capital firm, he helped a host of technology companies get off the ground.

These days, Mr. Khosla, 51, is still investing in technology, but much of it has nothing to do with the world of network computing in which he made his name. He is particularly excited about new ways of producing ethanol — the plant-derived fuel that, he says, could rapidly displace gasoline. "I am convinced we can replace a majority of petroleum used for cars and light trucks with ethanol within 25 years," he said. He has already invested "tens of millions of dollars," he said, in private companies that are developing methods to produce ethanol using plant sources other than corn.

Mr. Khosla isn't the only big-name entrepreneur to embrace ethanol. Sir Richard Branson, chairman of the Virgin Group, plans to invest $300 million to $400 million to produce and market ethanol made from corn and other sources, said Will Whitehorn, a director of the company. Virgin expects to announce soon the site of its first production facility, probably in the eastern United States, with a second one likely to follow in the West, Mr. Whitehorn said.

Bill Gates has also made a move into the ethanol market. Cascade Investment, Mr. Gates's private investment firm, has declared its intention to buy $84 million in newly issued preferred convertible securities in Pacific Ethanol, according to William Langley, its chief financial officer. The company, which is based in Fresno, Calif., and is publicly traded, says it hopes to become the leader in the production and distribution of ethanol in the Western states.

Ethanol derived from corn now accounts for 3 percent of the American automotive fuel market. Most cars in the United States can already handle fuel that is up to 10 percent ethanol, and as many as five million are so-called flex-fuel vehicles that can use a fuel called E85, which is 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline.

The current excitement over ethanol derives from research that has cut the cost of converting nonfood plant matter like grasses and wood chips into alcohol. Mr. Khosla says he believes that such ethanol, called cellulosic ethanol, will eventually be cheaper to produce than both gasoline and corn-derived ethanol.

Can investors whose pockets are not as deep jump into the ethanol market? Yes, but they are taking a big risk. Picking long-term winners among the companies that make ethanol — or, for that matter, develop other alternative energy technologies — is a very uncertain business. The few public companies that focus on ethanol are typically unprofitable. Pacific Ethanol, for example, has not yet had a profitable quarter and will not until at least the fourth quarter, when its first plant is scheduled to begin production, Mr. Langley said.

Few mutual funds focus on alternative energy companies. "We are not going to start a dedicated alternative energy fund, period," said Wenhua Zhang, a technology analyst at T. Rowe Price. The company is avoiding the sector "for the same reason we didn't start an Internet fund in 2000: a dedicated very narrow sector fund with a single focus typically has a much higher risk."

Some publicly traded companies with operations linked to ethanol include Novozymes and Danisco, both based in Denmark, and Diversa of San Diego; all three have said they have made major gains in reducing the cost of the enzymes needed to produce ethanol from cellulose. Bigger, more diversified companies like Archer Daniels Midland and Monsanto have ethanol operations, too, though ethanol is but one of many businesses for these giants.

Two mutual funds that focus on alternative energy include some ethanol companies among their holdings. The New Alternatives fund holds shares of Abengoa and Acciona Energía, two Spanish companies investing in ethanol production. Another option is the PowerShares WilderHill Clean Energy Portfolio, an exchange-traded fund that tracks a basket of 40 alternative energy companies. Robert Wilder, who created the index on which the fund is based, said that it currently includes just two companies with significant ethanol interests: Pacific Ethanol and MGP Ingredients, an ethanol producer in Atchison, Kan.

Mr. Wilder said he expects to add other companies involved with ethanol. "It's very elegant," he said. "We can take an agricultural waste product we currently pay to get rid of and convert it into fuel."

But many ethanol companies are privately held, making them inaccessible to most investors. And there is certainly room for skepticism about ethanol's future. After all, corn ethanol has been around for years, and even with a current spike in demand, the industry commands only a 3 percent share of the market. Mr. Khosla counters that soaring energy prices have made corn-based ethanol more competitive, while research advances in breaking down cellulose into simple sugars have cut the cost of making ethanol from other sources.

"Ethanol is cheaper to produce, unsubsidized, than gasoline today," he said. "As these technologies ramp up, they will be cheaper — unsubsidized — than gasoline even if petroleum drops to $35 a barrel."

Brazil has proved that ethanol can be made competitively from sugar, said Daniel M. Kammen, a professor in the energy and resources group at the University of California, Berkeley. He estimates the cost of producing ethanol from sugar — including raw materials and processing — at $6 to $7 per gigajoule (a unit of energy) versus $14 a gigajoule for gasoline. In Brazil, roughly 70 percent of new vehicles are equipped to handle ethanol, and the country has been able to curb its dependence on foreign oil and turn ethanol into a growing export industry.

But cellulosic ethanol, the kind produced from nonfood plant matter, has some advantages over food-based ethanol. Because cellulosic ethanol is derived from plant waste, wood chips or wild grasses like miscanthus and switchgrass, it would not require costly cultivation; that would mean savings on labor, pesticides, fertilizers and irrigation.

And it is superior to corn-derived ethanol in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, Professor Kammen said. He expects cellulosic ethanol to catch on quickly. "I think you can really see ethanol comprising 25 to 30 percent of gasoline consumption within 10 years," he said.

FOR that to happen, automakers would need to build more flex-fuel cars. The cost of adding this capability to new cars has been estimated at roughly $100 a vehicle. And ethanol would need to be much more readily available at gas stations. Mr. Khosla has been lobbying in Washington for government help in both areas.

Smaller investors may be advised to just sit back and study developing opportunities. "This is an area where investors have to be patient and build up slowly," Mr. Khosla said.

But he said the potential payoff justifies his own aggressive bets. And ethanol's success, he said, would mean that more energy spending would flow to rural America. "You get a fuel that's cheaper and greener than gasoline," he said. "It gives us energy security."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home